November Issue 1999

Weatherspoon Art Gallery Showcases

History of Dillard Collection of Art on Paper in Greensboro,

NC

In 1965, Dillard Paper (now xpedx) inaugurated an annual Art on Paper exhibition at the Weatherspoon Art Gallery in Greensboro, NC. In an effort to establish a collection of 20th century works on paper, Dillard also established a fund, which enabled the Weatherspoon to purchase select works from each Art on Paper exhibition. Today, the Dillard Collection numbers some five hundred works by some of the 20th century's seminal artists.

Starting on Nov. 14, and continuing through Jan. 23, 2000, the Weatherspoon Art Gallery will present the exhibit, Drawn Across the Century: Highlights from the Dillard Collection of Art on Paper.

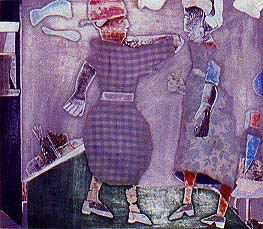

Beverly

McIver

Beverly

McIver

The Dillard Collection reflects the Weatherspoon Art Gallery's mission as a university museum committed to acquiring and showcasing work by contemporary artists. The collection includes art on paper from the turn-of-the-century to the present, and encompasses a diverse range of styles and techniques, from representation to abstraction, from pure drawing to composite and mixed-media works.

This thirty-fifth anniversary Art on Paper exhibition features seventy-five of the Dillard Collection's numerous gems organized by former curator of collections, Douglas Dreishpoon. Drawn Across the Century demonstrates the collection's remarkable breadth through works drawn from each previous Art on Paper exhibition. Works by Eva Hesse, Brice Marden, Jim Dine, Philip Pearlstein, Frank Stella, Louise Bourgeois, Romare Bearden, Christo, and William Beckman, among others, are included. A fully illustrated catalog is published in conjunction with the exhibition. It includes an essay by Joanne Moser, Senior Curator of Graphic Arts at the National Museum of American Art. (You can see a copy of this essay and color images from the exhibit on our web site at www.CarolinaArts.com, in our Special Features section.)

Moser will give a lecture titled Why Drawing? on Sun., Nov. 14 at 2pm. The lecture will be followed by the opening reception for Drawn Across the Century.

A family art program is scheduled for Sat., Nov. 20 at 2pm and will include a gallery tour of the exhibition and a hands-on art project which will introduce children ages 5 - 11 and their families to the creative possibilities of working with paper. The workshop will be taught by paper maker and educator Faye Collins. The program is free. For more information, please contact Pam Hill at 336/334-5770.

For further information check our NC Institutional Gallery listings or call the gallery at 336-334-5770.

Dillard's Paper Trail

by Douglas Dreishpoon, Curator, Albright-Knox Art Gallery and former Curator of Collections at Weatherspoon Art Gallery

It was 1965--in retrospect a propitious year for Greensboro attorney Herbert S. Falk, Sr. to approach Stark Dillard on behalf of the Weatherspoon Art Gallery to enlist his company's sponsorship for an exhibition that would showcase works on paper. The idea was to select works by artists from around the country and initiate an important contemporary collection.

By 1965, Dillard Paper Company, founded in Greensboro thirty-nine years earlier, in 1926, had emerged as one of the leading wholesale paper houses south of the Mason-Dixon line, with sixteen branches in five Southeastern states. Being an astute businessman, Stark Dillard would have recognized the potential benefits of associating his expanding company with a nationally-promoted project. If he didn't, his good friend Herbert Falk certainly did, and with a little cajoling the die was cast.

Falk's prominence in the community, along with his current presidency of the Weatherspoon Gallery Association, made him an effective intermediary between Dillard and the upper administration at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Motivated by a healthy sense of civic pride, Falk set out to muster the forces of business and culture. He seemed to realize, too, that grassroots philanthropy, especially between local businesses and cultural organizations, was the wave of the future--the tangible incarnation of John F. Kennedy's inspired appeal for self-help and public service. Given the auspicious circumstances, it's not surprising that he seized the moment and, with the eager cooperation of Weatherspoon director Bert Carpenter, converted Dillard to their plan.

In a town the size of Greensboro, a $10,000 gift to a local art museum was big news. The announcement, reported in the Greensboro Daily News on Sept. 20, was made jointly by UNCG Acting Chancellor James Ferguson and Falk, who articulated the gift's far-reaching implications "The Dillard gift will have a tremendous impact on art in our city and in our state. Well-known national artists will be encouraged to compete in Greensboro. All over the country business is fostering art, and the Dillard gift will encourage others in our area to follow suit."

Art on Paper, described as "a national competitive art exhibition," was open to all artists residing in the United States who produced unique, one-of-a-kind objects on paper. These included drawings (in graphite, pastel, and charcoal), watercolors, oil and polymer paintings, and monoprints, but excluded print editions and photography, both considered multiples. Each exhibitor could submit up to three works, which had to be sent to the Weatherspoon properly matted, without frames or glass. With no entry fee, more than 1,000 entries inundated the Gallery prior to the Oct. 1 deadline. These were juried by C. V. Donovan, director of the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign, whose previous experience organizing numerous Illinois Biennials made him a logical choice. An additional section of invitees comprised approximately one-third of the exhibition.

In spite of its short, three-week run from Nov. 1 to the 24 in the Weatherspoon's original galleries in the McIver Building, the first Art on Paper was hailed a success and became the prototype for subsequent projects. Of the $10,000 provided by Dillard, $3,500 went toward the purchase of juried works, $5,000 was used to acquire selected works by invitees, and the balance of $1,500 paid for general expenses, such as a modest brochure, invitations, etc. By the time the exhibition closed, twenty-five works had been purchased for the Dillard Collection, a major coup for a relatively young university art museum and a prescient direction for its permanent collection.

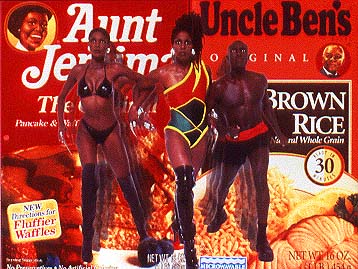

Renée

Cox

Renée

Cox

The creation of a works-on-paper collection made sense, pragmatically as well as pedagogically. It was still possible in 1965 to purchase significant works on paper for reasonable prices, and the originators of Art on Paper capitalized on this situation. Lee Bontecou's graphite study for the Lincoln Center Project, for instance, cost $150; a small, torn-paper collage by John Chamberlain came in at $450; one of Philip Pearlstein's early sepia and watercolor figure studies was acquired for $400; and an acrylic abstraction by Al Held was bought for $850. Additional works by Sidney Goodman, Nathan Oliveira, Paul Wonner, and Jimmy Ernst, all equally affordable, were also among the first acquisitions. Some of the most impressive collections of postwar art in this country were assembled by informed curators and directors, who, as the saying goes, were there at right time. The Dillard Collection is no exception; most of its stellar works were bought within a few years of the time they were made. This was certainly the case with Eva Hesse's string and ink wash drawing, which entered the collection in 1967, the same year it was executed, and was the artist's first work on paper purchased by a museum.

Robert

Colescott

Robert

Colescott

As the Collection expanded, so did its reputation. Faculty and students in the art history and studio art departments at UNCG were its primary beneficiaries, and as early as 1967, selections from the Collection began circulating to other educational institutions throughout the Southeast. Anyone who has ever worked with drawings knows their value as primary documents. The visual equivalent to an artist's handwriting, drawings tell us a great deal about the creative process. Artists use drawing as a way to generate and stockpile ideas. Even under the most austere conditions, drawing requires only a pencil, some paper, and an idea. Drawings constitute a unique genre, and every artist, whether a painter, sculptor, or printmaker, develops a personal rapport with it, even while exploring various techniques and media. The Dillard Collection, conceived first and foremost as a teaching tool that offered students an empirical, hands-on encounter with original works of art, continues to function in that capacity.

Roy

De Forest

Roy

De Forest

Since 1965 the Collection has expanded by anywhere from five to fifteen works each year depending on acquisition priorities and what has been available. It's easy to judge the Collection's merits in hindsight; stellar acquisitions have the ability to transcend the moment of their making, while others remain obscured by history's shadows. Hits are inevitably balanced by misses. In the end, though, it's the hits that count. The Dillard Collection, like any other of note, was built on speculation and moxie. Leaving aside the adage that buying contemporary art is ultimately a crap shoot, the Collection's diversity underscores a founding mandate to purchase work by emerging artists. This has been its most enduring legacy, the main reason for its continued vitality.

As the Collection nears its thirty-fifth anniversary and numbers 488 works, the time has come to celebrate its history by showcasing and publishing some of its holdings. I was guided in my selection by several criteria. I wanted the contents of the exhibition to reflect the Collection's chronological breadth, so each year, up to 1997, is represented by at least one work. I also wanted to highlight its impressive range of media, to demonstrate the multifarious nature of works on paper. I gravitated to works that stood out as exemplary not only for a particular artist but when measured against the history of drawing. Admittedly, another curator might have chosen differently, which is as it should be. A noteworthy collection lends itself to many presentations and interpretations. Someday the Dillard Collection will be published in its entirety, so that others, within and without the University, can know its full extent. Until then, this project samples of some of its greatest hits.

An Essay in Conjunction with the Exhibit,

Drawn Across the Century: Highlights from the Dillard Collection

of Art on Paper.

by Joann Moser

Why Draw?

Drawing has changed dramatically from its earliest manifestation in the fifteenth century, when the invention of paper in the West allowed artists to save preparatory drawings for works of art to be realized in another medium. As Arthur C. Danto has noted: "Until an affordable supply of paper allowed drawings to be saved or even done for their own sake, it was common for them to be destroyed, either in the course of transferring images to the panels on which paintings were to be executed or, if the drawings were done directly on those surfaces, by submerging them under layers of glaze or pigmented gesso."(footnote 1) As paper became more readily available to artists, the functions that drawings served increased gradually as well, until they came to be appreciated as works of art in their own right and to be executed by artists as finished works of art. Not only have the reasons artists make drawings multiplied, but the materials, techniques, scale, and styles of drawings have proliferated as well. The speed of change has accelerated considerably during the twentieth century, and the range of art that we now call drawing would surely baffle and disconcert our ancestors, even as recently as the end of the last century.

Although drawings have traditionally been associated with draftsmanship, or the making of lines or marks on a sheet of paper, twentieth century drawings frequently include color, collage, and printed elements. Watercolors and pastels, sometimes called paintings because of their reliance on color, are more frequently considered to be drawings because of their paper supports. So broad has this designation become that trying to define what is and what is not a drawing would be an exercise in futility. Complex combinations of techniques and materials further blur any simple definition of drawing. Substances as diverse as fabric, plastic, thread, newspaper, string, gesso paste, torn paper, seeds, and wax take their place next to graphite, ink, pastel, and charcoal as legitimate drawing materials in the drawings of the Dillard Collection.

If anything can be said to unify the diverse images, techniques, styles, and approaches to drawing represented in the Dillard Collection, it is the presence of the artist's hand that remains visible on each sheet. From the most precise academic study (Kenyon Cox, Figure of Astronomy, no. 12) to the most expressionistic marks (Franz Kline, untitled pastel, no. 35), the artist's individual touch remains apparent. Even in such an austere, geometric abstraction as Brice Marden's untitled graphite drawing (no. 46), careful examination of the solid black surface of the drawn square reveals a buildup of individual marks that enliven the otherwise severe, geometric form.

Similarly, Eva Hesse's untitled drawing from 1967 (no. 31) appears to be a mechanical system of repeated circles in a grid format, but the strictness of the regularity is relieved by the shadows cast by the cotton strings that protrude from the center of each circle. The gray of the ink wash, the lighter gray of the shadows, and the fine pencil lines that vary slightly from one to the next, as well as the differing shades of white paper and white string, endow the work with a subtle luminosity that belies the repetitious regularity of the composition and reveals the individuality of the artist's hand. Hesse's drawing is a delicate hybrid sculpture, the thread projecting from the two dimensional surface reminiscent of the tubes and ropes that characterize some of her most poignant work.

Both the drawing by Marden and the one by Hesse are complete works of art in their own right, related by idea and form to the artists' works in other media, but distinctly separate and independent. In the twentieth century, drawing has become an autonomous medium that has interested artists for its own qualities and possibilities, rather than simply as preparation for painting, sculpture, or architecture. Drawing has continued to fulfill the many functions it served in previous centuries, in addition to new ones it has assumed during the past century, and it has emerged from the shadows of other art forms to achieve recognition as an independent form of expression .

Drawings for Production in other Media

One of the oldest forms of drawing is the sketch for a work of art in another medium. As early as the fourteenth century, Cennino Cennini recognized that drawing provided the cornerstone of art, and from that time on, artists often saved their own drawings, although many early preparatory drawings have been lost because of the fragility of the paper on which they were executed.

Among the earliest works in the Dillard Collection is Kenyon Cox's Figure of Astronomy, one of many studies for a monumental mural in the Library of Congress. An academic drawing of the highest order, the sheet is squared for transfer with a grid that allowed the artist to enlarge it proportionately when he transferred the composition to its architectural setting. That Cox took the setting into consideration is evident from the perspective with which the figure has been rendered. Knowing the viewer would be looking at the figure from below, the artist adopted a relatively low vanishing point for the drawing to simulate the angle from which the figure in the mural would be seen. Although we have come to appreciate drawings such as this for their intrinsic value, clearly this drawing was never intended to be an independent work of art.

Similarly, William Beckman's Seated Model #1 is one of many studies from the model that he executed in preparation for a major painting, Classical Woman. The painting represented the first time the artist had worked directly from life since 1981 and took more than two and one half years to complete. Until that time, his figure subjects had been either himself or his wife, Diana, but the model for this painting was a young woman whom he had met socially.(footnote 2) The series of charcoal sketches he made of her, beginning in November 1988, were reductive studies of various poses, one of which he chose for the final painting. The individual drawings each served as an exercise in observation and composition in the long tradition of drawing studio models. Beckman paid little attention to rendering the individual features of the model, as he was not interested in depicting a specific person, but rather "a portrait of a gender."(footnote3)

Drawings for work in another medium are often done in series. It is especially informative when a drawing can be seen among others in the series-as in the case of the Untitled (Cubist Studies) by Blanche Lazzell-because they offer insight into the artist's creative process. Lazzell had several basic compositional elements in mind when she began this series, and the group of four drawings can be appreciated as variations on a theme. Of special interest is the way in which the artist changed the primary focus of the composition through the darkening of lines, shading, and the addition of textures.

Studies are especially important for sculptors, for whom they are often the first in a number of steps toward the realization of a finished work, or the only remaining record of an idea for a sculpture that never was executed. Ronald Bladen (no.6), Donald Judd (no. 33), and Theodore Roszak (no. 58), like most sculptors, relied on drawings to visualize their three-dimensional work. Bladen's Study for V, as with Roszak's four views Rectilinear Space Construction. are crystallizations of an idea, a blueprint for the realization of the final piece.

Robert Smithson's Hypothetical Continent of Lemuria (no. 63) represents the artist's conception of a place that might have been and might be recreated with shells from the shores of Sanibel island. The specificity of the maps and diagrams contrast ironically with the speculative nature of an idea that was never intended to be carried out, but exists only in Smithson's fertile imagination and, of course, this drawing.

Drawing as a Visual Record

There are some artists, among them Charles Burchfield, who chose to work almost exclusively on paper. Burchfield's early training emphasized watercolor painting, and though he learned to paint in oil, he was never entirely comfortable with the medium and completed fewer than two dozen oil paintings. Instead, he preferred the touch of applying watercolor to paper as well as the transparency of watercolor, and made hundreds of pencil sketches that served as studies for his watercolors. Burchfield lovingly saved his drawings and catalogued them carefully so he could return to them for reference long after they were made. House and Trees (no 9) is a typical study by the artist of his immediate surroundings, possibly a view from his own house or back yard, elements of which he might later incorporate into a larger, more complex watercolor composition. Yet even in such a simple sketch, Burchfield suggests meaning in the juxtaposition of the slender, irregular, organic forms of the trees and the solid, regular, geometric forms of the houses behind them. Emphasizing the repeated horizontal slats of the wooden houses and the regular rungs of the two ladders leaning against the house, he juxtaposed manufactured boards to wood in its natural state as trees Separated by the delicate row of gnarled branches and hewn fence posts that form a barrier between the built environment and the natural environment, Burchfield reinforced the contrast through the distant figure of a man on the roof and the suggestion of a cat and a squirrel amidst the trees in the foreground .

Burchfield's sketches served as studies for his watercolors, as visual records of the particular scenes he wished to document. One of the most important traditional functions of drawing, especially before the invention of photography in the mid-nineteenth century, was mimesis, the accurate representation of an object, a person, or a scene. Artists recorded botanical, zoological, and anatomical specimens, and often accompanied explorers to record what they discovered. Artists were sent to battlefields and important historic events. Paper was the most portable of materials, and the drawings that resulted were valued as much for the information they conveyed as the skill with which they were executed.

Even as photography gradually assumed some of the mimetic function of drawing, artists continued to draw as an "aide-memoir," whether to capture a particular composition, a special color harmony, or a specific expression. Indifferent to realistic or naturalistic representation, they often recorded only those aspects of a subject that interested them.

George Ault, for example, depicted a specific location in his watercolor Waterfront, St. George. Bermuda (no 2). What appears to have interested him most is the distinctive quality of light and its softening effect on colors and edges, a tranquil scene of man and nature in harmony. The composition suggests that the artist's vantage point might be from a boat like the two shown in the middle ground. By contrast, Louis Lozowick's depiction of Gas Tanks (no. 44) presents a more generalized view of his subject, emphasizing the geometric precision of man-made constructions and the domination of man over nature. Although some specifics of the location are included, such as the tall, narrow building that abuts the tanks, the view is filtered through the artist's own interpretation of the subject.

While Lozowick's depiction of gas tanks shows an idealized representation of his subject, Joan Brown's depiction of Manual and Mary Julia (no. 8) depicts two specific people at night in an identifiable place, inside an apartment in a city with tall buildings. Yet the details of their appearance are subordinated to the overall composition and the patterns in the room. It is the relationship between the two figures that interests the artist and provides the focus of the composition.

Alfred Leslie's sketch of his wife, Constance West (no. 40), also eliminates all extraneous details to present a stark, frontal, almost iconic figure posed in a harsh light that models the form. A realist who sought to "restore the practice of pre-twentieth century painting . . . that demanded the recognition of individual and specific people," Leslie "rejected photography for any kind of use in my work, after working with it in my earlier transitional paintings, mainly because the photograph tends to underline the belief that people cannot trust and accept what they see without the verification by some form of mechanical instrumentation." (footnote 4)

In contrast to Alfred Leslie, who used drawing as a means to recapture the integrity of the Renaissance and Baroque traditions, Richard Prince subverts that tradition by appropriating another photographer's work as the subject of his drawing (no. 56). Beginning in the late 1970s, Prince, among others including Sherrie Levine and Louise Lawler, became one of the leading artists who initiated the radical practice of rephotography, photographing another person's photograph, or in Prince's case, advertisements, as the subject of their work. Challenging traditional notions of subjectivity, originality, and authorship, he used photographic means to question and confront the conventions of fine art photography.5 While artists have used photographs as studies for their paintings since the nineteenth century, they were interested in the subject of the photograph rather than the photograph as an object. Prince, on the other hands draws the photograph itself; the subject of the photograph is of secondary concern.

Drawing as Discipline

Although its intention is quite different, Prince's act of drawing a photograph is not entirely unlike the more traditional function of drawing as a discipline. Since the Renaissance, drawing has been considered the foundation of all the visual arts. By the nineteenth century, art training followed the same basic pattern, whether it took place in a master's workshop, a private art school, or a public academy. The student began by copying two-dimensional works, such as drawings or prints. After mastering this skill, the student was allowed to move on to represent three dimensional forms by copying antique sculptures or plaster casts. Only after these skills were mastered was he allowed to draw from life in the form of a studio model. Supplemented by the study of anatomy, geometry, and perspective, an artist's training was based on a solid mastery of drawing skills that he called upon throughout his career, regardless of the medium in which he was creating. As an artist matured, however, he often broke from the rigid rules of academic drawing to transform the process into a more personal expression.

By the late nineteenth century, some art schools began to question the traditional approach to drawing, although drawing remained the foundation of an artist's studies. Yet many artists continued to recognize the value of the traditional approach, both for the discipline it imposed and for the potential elegance of the finished picture. Edwin Dickinson's Florentine Cast (no. 16), for example, is an exquisite graphite drawing in the tradition of Ingres, subtly modeled without a single stray mark to betray the artist's hand. Executed by the artist at the age of 22, when he was a student at the Buffalo Fine Arts Academy, this drawing demonstrates how early in an artist's career these skills can be attained, serving as the basis for all later work. As Dickinson's painting style developed, he moved away from such a linear, academic approach toward a more spontaneous, painterly expression, but the discipline of his early drawings remained the underpinning of his more impressionistic style.

If academic drawing from a sculpture or cast represents one form of discipline, then an artist's choice of medium can also represent a sort of self-imposed discipline. Consider, for example, the exquisite silverpoint drawings of John Storrs, such as his portrait of General Nicolas Golejewski (no. 66), executed in a medium that allows for-no mistakes. A silverpoint drawing is made on a prepared sheet of paper, coated with a substance that provides friction, or "tooth," when a piece of silver is dragged across its surface. Particles of silver are deposited on the ground, creating a delicate silver line wherever the silver pointed stylus has come into contact with it. If too much pressure is applied, the point will penetrate the ground, resulting in a line the color of the paper beneath. Once the silver is deposited, it cannot be erased or removed, unlike a pencil line on paper, so the artist must be skilled and sure enough to draw it correctly on the first try. Since additional pressure cannot be used to darken a line, delicate hatching lines are used to create shadows and emphasis, as Storr did under the sitter's chin and beneath his lapels. Despite the limitations of silverpoint drawing, however, the delicacy of line and subtlety of nuance that can be achieved by a master draftsman are incomparable. Over time, the silver deposited on the surface will oxidize, creating a warmer tone than the original line.

Joseph Stella was another artist who frequently challenged his own virtuosity as a draftsman by working in silverpoint At the same time he created exquisite silverpoint drawings, primarily portraits and flower compositions, he seemed to reject the delicacy and preciousness of the silverpoint technique by creating collages from dirty, torn, wrinkled, or waterlogged pieces of discarded paper. Using debris he found in the street as the natural equivalent to Marcel Duchamp's "ready mades," Stella bypassed his own technical skill as a painter and draftsman to create art based purely on his eye and his imagination. His Chicklets collage (no. 65), composed of two soiled chewing gum wrappers placed side by side in the center of a white field, is especially revealing. The prepared white surface on which the two torn and dirty wrappers are glued is the same surface that Stella used for his elegant and pristine silverpoint drawings. In his collages, the artist set himself the challenge to create balanced, subtle compositions that belie the lowly materials from which they are made and transform them into the precious materials of art through the sheer force of his imagination. Substituting creativity and vision for the technical virtuosity that had characterized his other drawings, Stella asserted that vision, rather than skill, was the essence of a work of art.(footnote 6)

Drawing as Imagination

Romare

Bearden

Romare

Bearden

The Dillard Collection is especially rich in collages that bridge the realms of art and life in a way that few other media are able to do. From the strictly formal arrangements of shape, texture, color, and text of such works as Bradley Walker Tomlin's untitled collage (no. 70) and A.E. Gallatin's Composition (no. 23), to the more pictorial compositions of Romare Bearden's Conversation Piece (no. 3) and Konrad Cramer's Untitled (City Street) (no. 13), the creation of a collage challenges an artist to transform the concrete, mundane materials of daily life into a composition divorced from their original identity while exploiting certain aspects of it. Hence Cramer attaches the Gargoyle label to the side of a drawn building and uses a rubbing of a coin to suggest a sun, injecting his sense of humor into an otherwise formal cityscape.

For many artists, the directness and immediacy of working on paper fosters a sense of spontaneity that is sometimes inhibited in other media. By comparison with painting or sculpture, the informality of drawing allows the artist to experiment with ideas that might not work, without investing a significant amount of time or materials. A drawing is usually a more private creation in which an artist can experiment with ideas that might not be acceptable in a more public form. It allows for a degree of spontaneity and ease of expression that stimulates the artist's imagination. It has been observed that "drawing helps the development of an idea in much the same way as thoughts can be clarified by being put into words.... The act of converting an idea into lines and other marks on paper often excites the mind and frees the imagination, encouraging the flow of creative thought."(footnote 7)

John Graham's drawing Anna di Forli is a profile portrait drawn from life of his friend Anna Saporette. By giving her a fanciful name and exaggerating certain prominent features, such as the elongated neck, the artist transforms a study of a particular person into an idealized portrait that recalls Renaissance precedents.(footnote 8) At the same time, he undermines his own idealization by adding a prominent gash in her neck that adds an element of imperfection, even violence, to her otherwise classical beauty. Jarring the viewer's expectations with this startling wound, the artist transforms the elegant portrait into an uneasy projection of his own imagination.

Even further removed from reality are Jim Nutt's distortions of human anatomy and visual perspective in His Legs and Her Hair (no. 53). The cartoon-like figures suggest a scene on a stage in which the two main figures appear to confront each other. The scene is electric with tension, suggested not only by the confrontational poses, but by the short, repetitious lines that delineate the stage curtain and the figures themselves. Their jagged energy animates the drama, making concrete the uneasy distortions of the forms. Carefully conceived in the artist's mind, this spare, lively drawing gives credence to the adage, "a picture is worth a thousand words." Straight from the artist's imagination to the piece of paper, this drawing gives form to implausible musings with directness and clarity.

Just as it would be difficult to translate the implied narrative of Nutt's scenario into words, the juxtapositions of Jane Hammond's mixed media drawing Tricky Finger (no. 29), suggest a variety of possible relationships and meanings that engage the viewer's imagination and creativity. The images were carefully selected and placed in relation to one another, yet the work conveys a sense of spontaneity and chance that challenge the viewer to simultaneously seek and create meaning from the disparate elements, many of which depict or refer to puzzles. Some of the forms are readily identifiable and clearly outlined in black, while others are shadowy and indistinct, suggesting a visual confirmation of the many levels of meaning that the composition holds. The mixed media composition combines not only drawing, painting, and printmaking techniques, but incorporates commercial processes, such as color Xerox and lino blocks, as well as crayon and transfer images that are usually associated with children's art. Although the "tricky finger" of the title appears to refer to the brightly colored finger image and the games, puzzles, and illusions depicted in the composition, perhaps it is also a reference to the artist's sleight of hand in combining such a variety of techniques and images into a single work that defies simple definitions or interpretations.

The spontaneity of drawing holds special appeal for artists whose primary work does not allow for unpremeditated decisions. Sculptors, for example, usually work from sketches or maquettes, with only modest opportunity for changes or improvisation. Those who work with metal or stone or blocks of wood can rarely add more than variations or refinements to an idea once the basic shape has been created. Drawing represents a sense of freedom, unencumbered by the materials and technical demands of most sculptural media. Louise Bourgeois' Drawing #1 (no. 7) dates from a time when the artist was making a transition from painting to sculpture. In her 1953 solo exhibition at the Peridot Gallery, she showed a large group of evocative India ink drawings, which "suggests masses of wavy hair, cross sectional diagrams of rock strata, the rolling movement of a heavy sea.... intertwined corn husks, or of muscles and sinews...."(footnote 9) in contrast to her earlier drawings from 1951, many of which appear to be possible ideas for sculpture, the drawings of 1953 seem to be more purely flights of the imagination, inspired by real objects and phenomena.

If drawings provide an unparalleled opportunity for imaginativeness, they also provide an equally important opportunity to visualize rational thought. Sol LeWitt has written: "In Conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work.... If the artist carries through his idea and makes it into visible form, then all the steps in the process are of importance. The idea itself, even if not made visual, is as much a work of art as any finished product. All intervening steps-scribbles, sketches, drawings, failed works, models, studies, thoughts, conversations-are of interest. Those that show the thought process of the artist are sometimes more interesting than the final product."(footnote 10)

Blanche Lazzell's four untitled Cubist studies (nos. 39a-d) in the Dillard Collection reveal the truth of Lewitt's statement. In contrast to Lewitt's presentation of a conceptual model, Lazzell's studies are experimental and empirical. While each one can stand on its own as a drawing, the real interest lies in the relationship of one to the next, revealing how the artist thinks as she develops an idea. The successive states of printmaking offer a similar view into the artist's creative process, but the intimacy of drawing, the directness with which the artist made marks on the paper, conveys an even more immediate sense of the artist's presence and ideas.

Drawings as Finished Works of Art

Until the twentieth century, few drawings were executed as completed works of art. Although drawings were valued by collectors since the Renaissance, they were appreciated primarily as private works of art, intimate in scale and limited in ambition. Portraits in pastel and watercolor paintings were exceptions, and were collected and displayed as finished works of art in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. By the twentieth century, however, it became much more common for artists to execute finished works of art on paper in a variety of media.

To some extent this development was influenced by the larger size papers that became commercially available in the nineteenth century. Max Weber's In the Woods (no. 73) is comparable in size to many of his easel paintings of that time. A fully realized Cubist composition, this pastel drawing takes advantage of the rich colors of the pastel medium as well as the traditional drawing technique of allowing the color of the bare paper to function as an integral aspect of the composition. As ambitious in scope and resolution as a painting, this pastel and others like it take their place in Weber's oeuvre as independent works of art side by side with the artist's oil paintings.

Pastel and watercolor continued to be the techniques most closely associated with finished works of art, probably because they most closely approximated the color possibilities of oil painting. The Dillard Collection generously reflects this important role of pastel drawing in such works as Franz Kline's two untitled drawings (no 35a and b), Jim Dine's A Hand-Painted Tie (no. 19), Charles Long's Among the Dead (no. 43), Jan Muller's Don Quixote and Sancho Panza (no. 52a and b), Lucas Samaras' untitled pastel (no. 60), Morton Schamberg's Composition (no. 61), and Ethel Schwabacher's Blow Upon My Garden (no. 62). Similarly, watercolors by such leading modernist artists as Arthur B Dove, Jan Matulka, Charles Burchfield, Charles Demuth, and John Marin during the first half of the twentieth century laid the groundwork for greater acceptance of works on paper as fully independent works of art.

Color was an important element in the creation and initial acceptance of drawings as autonomous works of art, but artists recognized that black and white could communicate a strength of expression from which color might detract. For example, the boldness of Lee Krasner's lines and gestures in the untitled ink drawing in the Dillard Collection (no. 36) conveys a power that would be diluted by the addition of color. If black and white have extraordinary potential for bold expression, their possibilities for subtlety and nuance, as in Eve Hesse's extraordinary collage, engage the viewer just as fully.

Although some artists relegate drawing to a specific role in their creative process, most recognize multiple roles for drawing, and a single drawing often serves multiple functions for the artist. As a teacher, Philip Guston emphasized the importance of art history and drawing as the fundamental prerequisites for a painter and encouraged life drawing as the basis for the development of a personal style. As an artist he turned to drawing as an expressive medium in its own right, as a means to explore themes and compositions before painting, and as a structural element in painting. According to Magdelena Dabrowski, Guston was also "deeply conscious of the inherently expressive, almost symbolic, character of the basic physical aspects of drawing, such as line and color or the absence of color."(footnote 11) Line is at the heart of Guston's drawings, and the quality of his line, even more than the forms it depicted or suggested, is the key to a drawing's expressive power. In Maverick Landscape the jaggedness of the line, the range of black from light to dark created by varying his pressure on the drawing tool, and the speed at which the lines were drawn impart expression to forms that are only suggested. Guston created this drawing at a time when he was moving from 'pure' abstraction to a more figurative language: "I remember days of doing 'pure' drawings immediately followed by days of doing the other, drawings of objects.... It was two equally powerful impulses at loggerheads."(footnote 12)

Drawings have rarely achieved the recognition and market value of paintings, but their increasing popularity among artists in the second half of the century, often in combination with other media, is indicative of the important new role they play in contemporary art. Their expanding scale, the variety of materials and combinations of media that characterize so many of them, as well as their multiple functions reflect the post-modernist attitude in which boundaries between media are blurred, often through the combination of several media in a single work. The traditional hierarchy of the arts, which places painting and sculpture above drawing, printmaking, photography, and video, is being challenged on several fronts. Since the 1940s, an increasing interest in process, concept, seriality, impermanence, and hybridization have provided viable alternatives to the authority of the singular masterpiece. No longer an adjunct of painting and sculpture, drawing has assumed an expanded role in the repertoire of the contemporary artist.

Joann Moser is the Senior Curator, Graphic

Arts for the National Museum of American Art

1. Arthur C. Danto, "Cabinet of Wonders:

A Personal View of Works on Paper," "On Paper,"

vol. 1, no 3, Jan-Feb. 1997, 2-3.

2. The young woman was a pianist and songwriter, and she agreed

to pose for the same hourly fee she received for piano lessons.

3. Penelope Hunter-Stiebel, "William Beckman: Dossier of

a Classical Woman," (New York: Stiebel Modern, 1991) 10.

4. Alfred Leslie, "Artist's Statement," in "Alfred

Leslie," (Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, 1976) 2.

5. Lisa Phillips, "People Keep Asking: An Introduction,"

in "Richard Prince" (New York: Whitney Museum of American

Art, 1992) 30.

6. Joann Moser, "The Collages of Joseph Stella: Macchie/Maccine

Naturali," "American Art," vol. no 3, summer 1992,

70.

7. Susan Lambert "Reading Drawings" (New York: Pantheon

Books 1984) 77.

8. This drawing is a companion piece to a portrait drawing of

her husband Adolfo Saporette fancifully titled "Adolfo of

Ravenna," also in the Dillard Collection. The two drawings

have been hung in the Weatherspoon Art Gallery facing each other

in the manner of traditional Renaissance double portraits.

9. James Fitzsimmons, as quoted in Deborah Wye, "Louise Bourgeois,"

(New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982) 21.

10. Sol LeWitt, "Paragraphs on Conceptual Art," "Artforum,"

summer 1967, 80-83.

11. Magdelena Dabrowski, "The Drawings of Philip Guston,"

(New York: The Museum of Modern Art 1988) 44-45.

12. Philip Guston, as quoted in Robert Storr, "Philip Guston,"

(New York: Abbeville Press, 1986) 44.

Mailing Address: Carolina Arts, P.O. Drawer

427, Bonneau, SC 29431

Telephone, Answering Machine and FAX: 843/825-3408

E-Mail: carolinart@aol.com

Subscriptions are available for $18 a year.

Carolina Arts is published monthly by Shoestring Publishing Company, a subsidiary of PSMG, Inc. Copyright© 1998 by PSMG, Inc., which published Charleston Arts from July 1987 - Dec. 1994 and South Carolina Arts from Jan. 1995 - Dec. 1996. It also publishes Carolina Arts Online, Copyright© 1998 by PSMG, Inc. All rights reserved by PSMG, Inc. or by the authors of articles. Reproduction or use without written permission is strictly prohibited. Carolina Arts is available throughout North & South Carolina.